Shooting T-Max 3200: Preparation, Discipline, and Trusting the Dark

Most people think shooting 3200-speed film is about cheating the dark.

It’s not.

It’s about preparation, restraint, and knowing exactly where the darkness breaks.

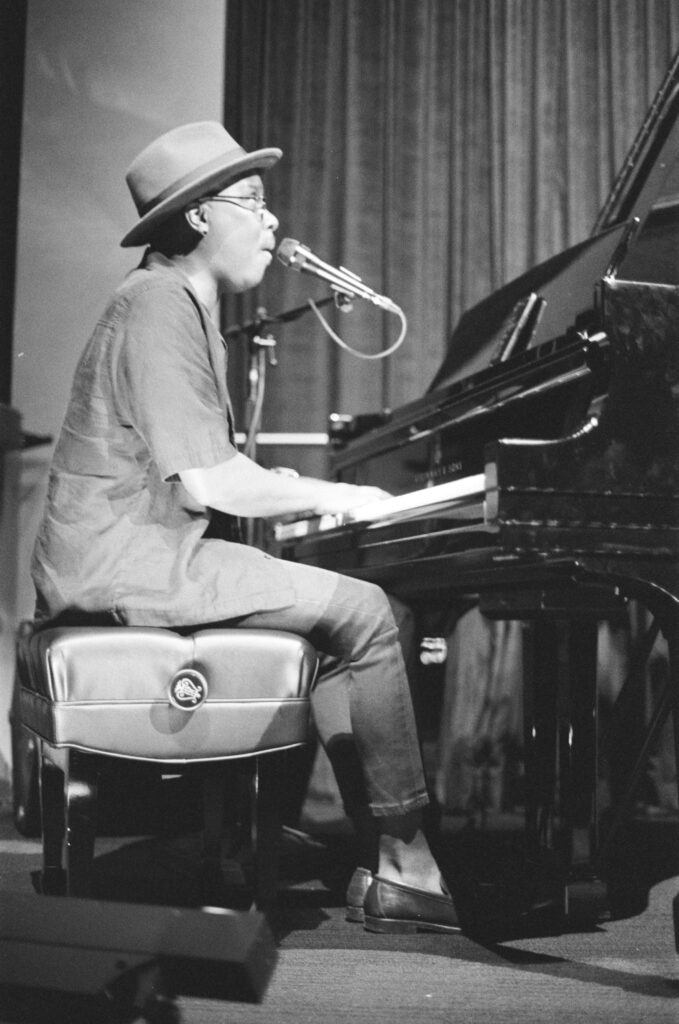

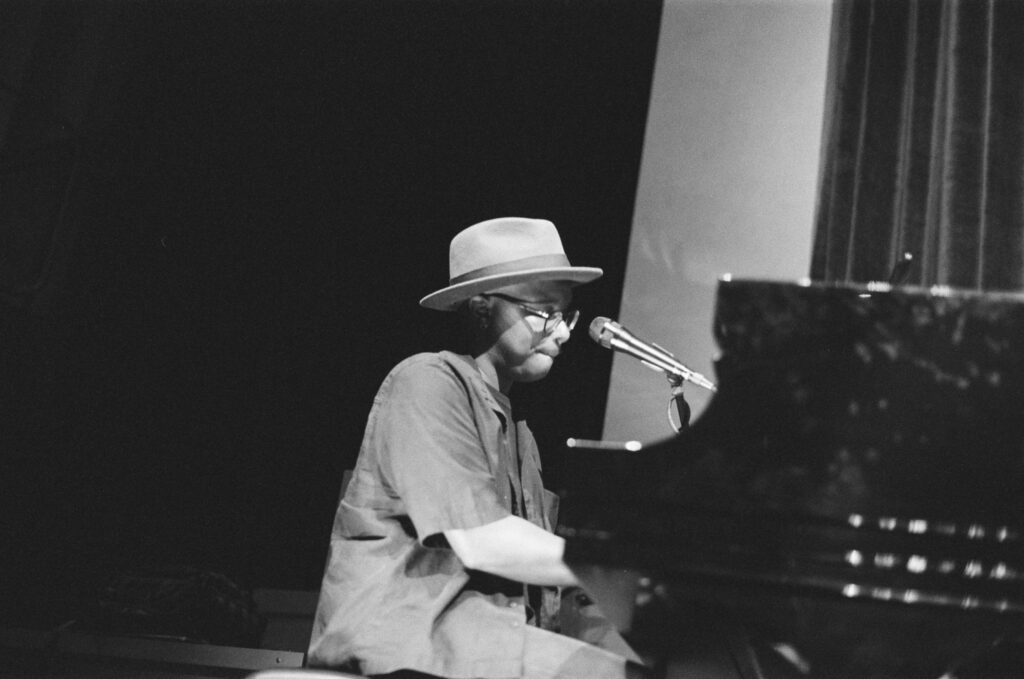

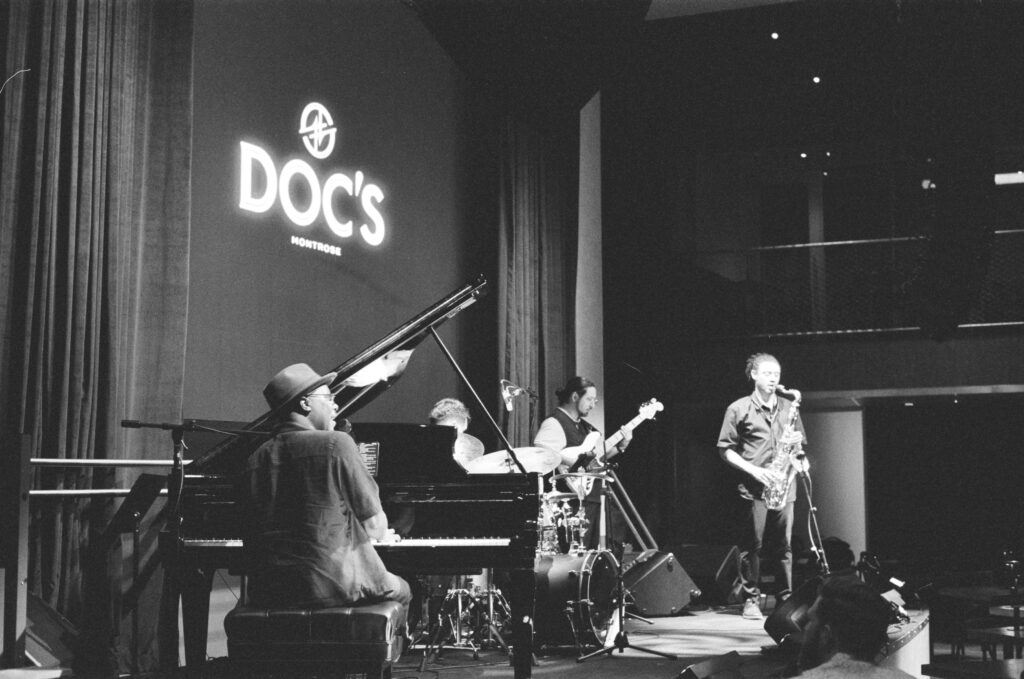

When I photographed Doc’s Jazz Club on Kodak T-Max 3200 with a Canon AE-1 Program, the work didn’t begin until the band took the stage. It started the night before—quietly walking the room while it was empty, listening to the space before it had a sound.

The Night Before: Walking the Club

I went to Doc’s the night before opening, not to make photos, but to understand the room.

No camera pressure. No musicians. No audience energy to distract me.

I walked the club slowly—bar, tables, stage left, stage right, behind the piano. I looked at how the practical lights fell, where the shadows swallowed detail, and where reflections would blow out faces if Iweren’tt careful. I took EV readings everywhere I thought I might stand the next night.

Corners.

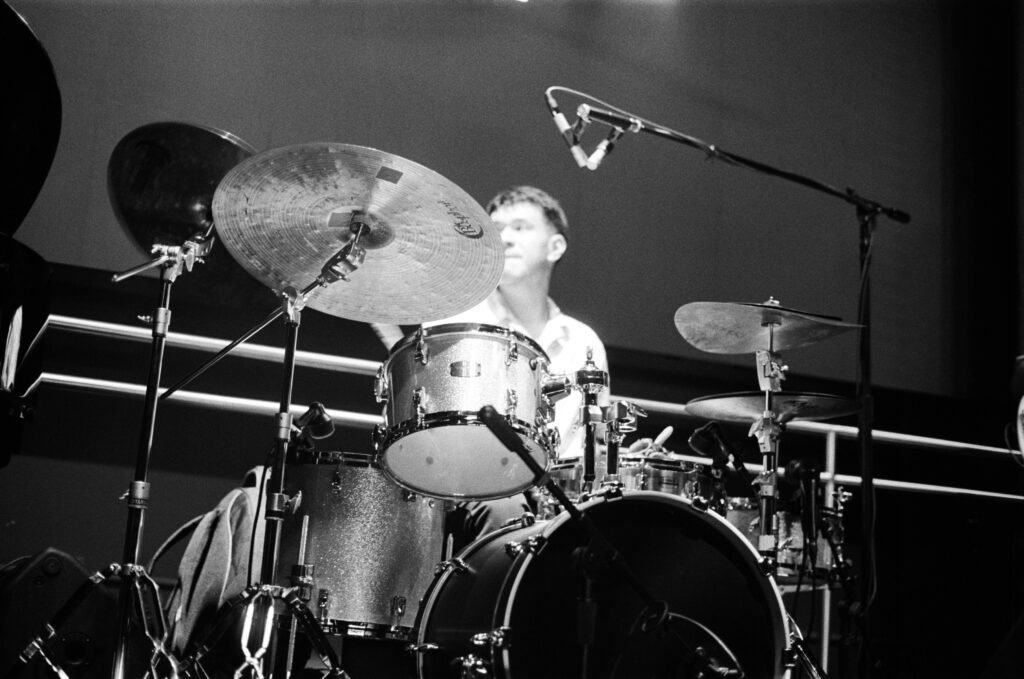

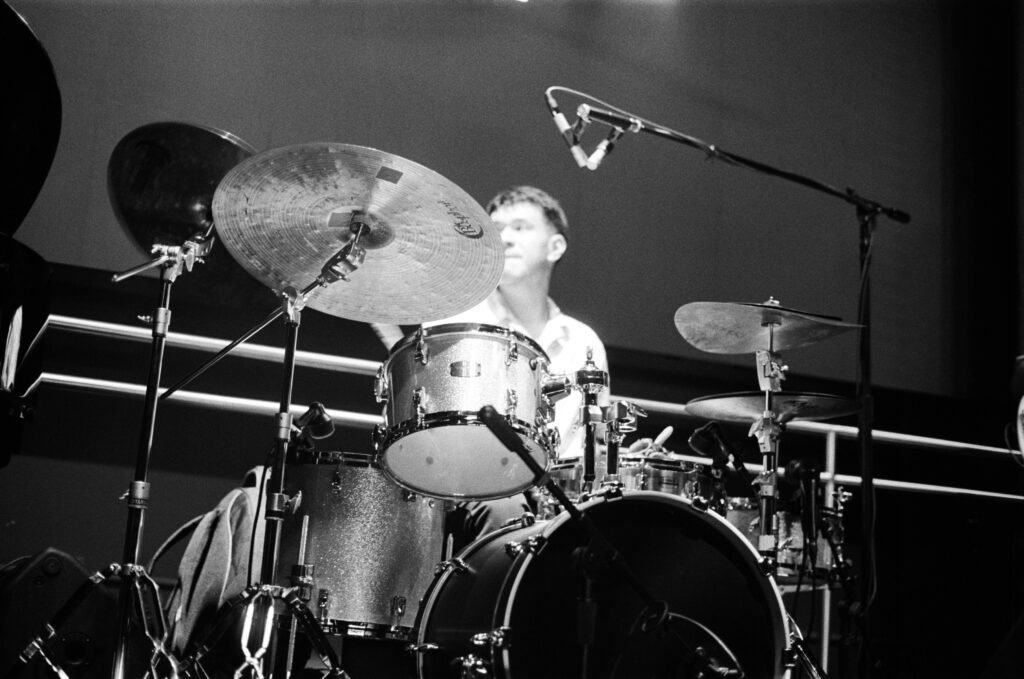

Behind the drummer.

Near the piano bench.

Back of house, looking toward the stage.

I wrote them down.

Why This Matters (Instructional)

Jazz clubs don’t have “one exposure.” They have zones.

If you meter once and assume the room is consistent, you’ll miss shots.

By pre-walking the space:

- You learn the EV range, not just a single number

- You identify where 3200 speed is enough — and where it isn’t

- You avoid panic metering once the show starts

This is especially important with a camera like the AE-1 Program, which provides honest feedback but won’t prevent flawed assumptions.

Choosing the Tool, Not the Hype

The camera was deliberate: Canon AE-1 Program.

Not a modern body.

Not a meter with matrix wizardry.

Just a solid, honest camera that tells you exactly what it’s thinking.

The film: Kodak T-Max 3200, shot at box speed.

I didn’t want the exaggerated contrast of an extreme push. I wanted smooth shadows, textured blacks, and highlight control—especially on faces and instruments. Jazz lives in midtones. Overcook those, and you lose the soul of the room. Fast film doesn’t mean reckless film.

Instructional Note on Film Choice

T-Max 3200 at box speed:

- Holds highlights better than most people expect

- Keeps grain structured, not clumpy

- Gives you flexibility without forcing contrast

Pushing further can work—but only if you want harder blacks and more aggression. For Doc’s, restraint mattered more than grit.

The Day Of: Everything Dialed Before the First Note

When the night came, I didn’t meter from scratch. I already knew the room.

That changes everything.

Instead of chasing exposure, I could focus on timing.

I knew:

- Where I could handhold safely

- When I’d need to brace

- Which angles would survive wide open

- Where reflections would betray me

I mainly stayed manual. The AE-1 Program’s meter was there to confirm—not to decide.

Practical Settings Philosophy

I wasn’t married to one shutter speed or aperture. Instead, I worked within a known exposure window:

- Shutter speeds fast enough to suggest motion, not freeze it completely

- Apertures open enough to gather light, but not so open that focus became guesswork

- Meter readings used as a reference point, not a command

This approach keeps you fluid instead of reactive.

Shooting Jazz Is About Respecting the Moment

I didn’t move constantly.

That’s something digital trains people to do—hunt, spray, repeat. Film slows you down. Jazz demands the same respect.

I waited for:

- Eye contact between players

- Shoulders leaning into a phrase

- The drummer lifts before the strike

- The piano player’s hat dipped as the room went quiet

Those moments don’t last long, but when you know your exposure, you can see them coming.

That’s the difference preparation makes.

Instructional Takeaway

If you’re constantly adjusting settings:

- You’re late

- You’re reacting

- You’re missing rhythm

Expose your brain early to lock so it can focus on gesture, timing, and emotion.

Why 3200 Speed Film Works Here

T-Max 3200 doesn’t scream. It whispers with confidence.

The grain isn’t an effect—it’s structure. Blacks stay deep but detailed. Highlights bloom without collapsing. Skin tones hold, even under stage lighting that would destroy slower stocks.

At Doc’s, the film handled:

- Hot stage lights

- Deep audience shadows

- Smoke, reflections, and motion

And it did so without calling attention to itself.

That’s the point.

Fast film isn’t about proving you can shoot in the dark. It’s about letting the room look the way it felt.

Trusting the Process (and the Film)

By the end of the night, I wasn’t thinking about settings.

That’s the goal.

When preparation fades into instinct, you stop photographing light and start photographing music.

When the negatives came back, they confirmed what I already felt:

- The room reads

- The moments land

- The grain belongs there

Nothing feels forced.

Final Thoughts

Shooting T-Max 3200 isn’t about bravery—it’s about discipline.

Walk the space.

Learn the light.

Respect the room.

Then let the film do what it was designed to do.

Doc’s Jazz Club deserved that kind of attention. And film—high-speed film—rewards it.

These images aren’t about noise or darkness.

They’re about being ready when the music starts.

December 20, 2025

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

@2025 copyrighted | created with brains

Based in HTX | travel Nationwide

jasonr@projectagbrmedia.com

Be the first to comment