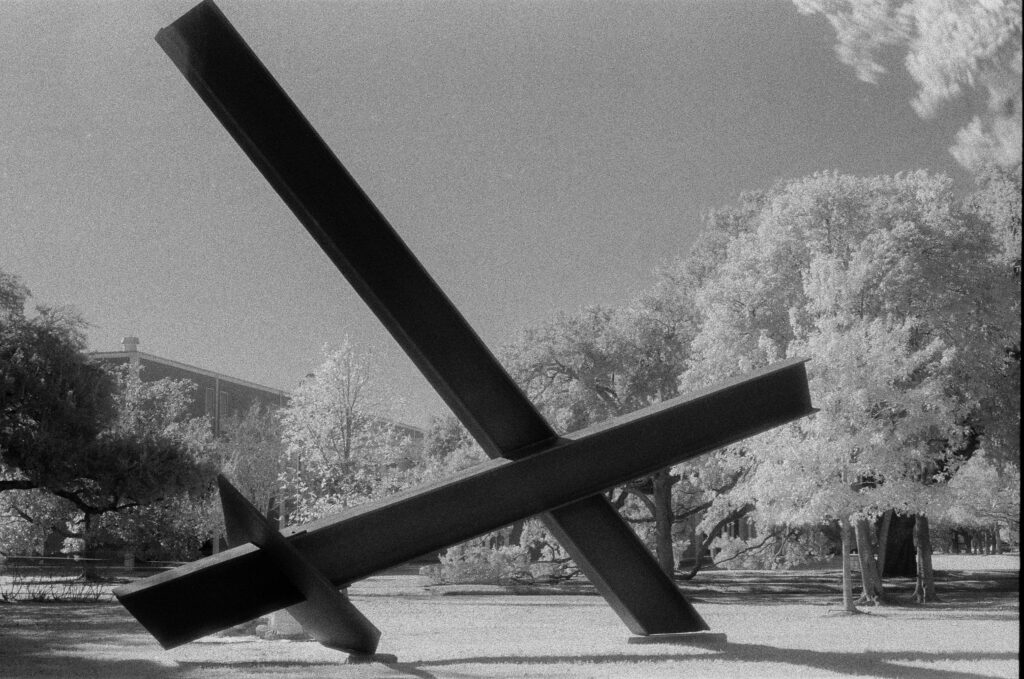

Ilford SFX 200 Infrared Film Review: Infrared as a Discipline with Hoya R72 Red Filter

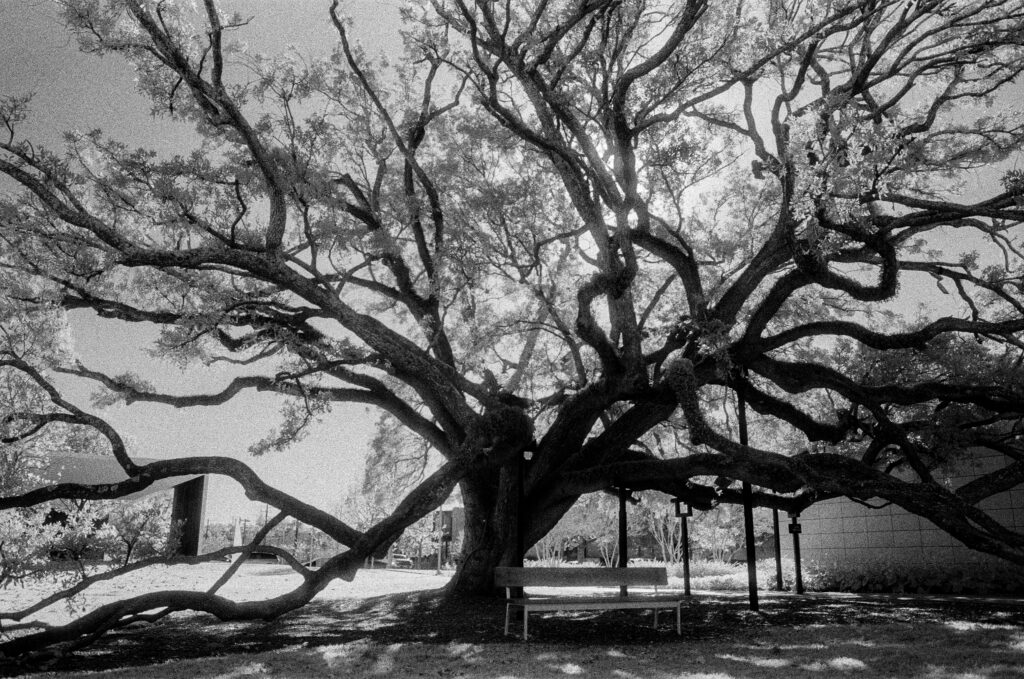

Infrared photography isn’t about effects. It’s about control under uncertainty. Once you remove visible light from the equation, you’re no longer responding to what your eyes see — you’re responding to how materials, vegetation, and atmosphere interact with wavelengths just beyond human vision.

This body of work was created as Part 1 of a three-part infrared film series, testing the currently available infrared-capable black-and-white films under the same conditions, with the same camera, lens, filter, and working method. The goal wasn’t novelty. It was consistency — and learning how each emulsion behaves when pushed into the near-infrared spectrum.

This first chapter focuses on Ilford SFX 200, a film that occupies a unique middle ground between conventional panchromatic black-and-white and true infrared materials.

The Camera and the Constraints

All images were shot on a Canon T90, paired with a Canon FD 28mm f/2.8 lens, mounted on a tripod for every exposure. The lens choice was deliberate: moderate wide-angle, minimal distortion, strong stopped-down performance, and predictable flare behavior.

Infrared demands mechanical stability. Once exposure times move into multi-second territory — especially in daylight — handheld work stops being expressive and starts being careless. Every frame here was shot at f/8, with shutter speeds ranging from approximately 2 to 6 seconds, depending on subject reflectivity and sky conditions.

The constant across the entire roll was filtration.

Why the Hoya R72 Changes Everything

A Hoya R72 is a deep red filter that blocks nearly all visible light, transmitting wavelengths roughly 720nm and above. Once mounted, the viewfinder goes effectively black. This immediately forces a change in workflow:

- Compose first

- Focus without the filter

- Lock focus

- Mount the filter

- Expose blindly

This sequence matters. Infrared photography punishes indecision. You can’t “fine-tune” composition once the filter is in place — you either trust your setup or you don’t take the shot.

The filter also breaks light meters.

Why the Film Was Rated Around ISO 6

Ilford SFX 200 is rated at ISO 200 in visible light. That rating becomes meaningless once a deep red filter is introduced. The R72 removes so much visible spectrum that in practical terms the film behaves several stops slower.

Rather than relying on filter factor math alone, the film was intentionally rated around ISO 6. This wasn’t guesswork — it was a decision made to protect shadow detail and preserve tonal separation. Infrared scenes tend to have extreme contrast: foliage reflects strongly, skies drop, and man-made materials absorb unpredictably.

Dragging the ISO down slows the exposure enough to:

- Prevent crushed shadows

- Avoid highlight clumping in foliage

- Give architecture weight instead of letting it float

This is less about “correct exposure” and more about usable negatives.

What Ilford SFX 200 Actually Is

Ilford SFX 200 is not a true infrared film. That’s often misunderstood — and it’s exactly why it’s valuable.

SFX 200 is a medium-speed black-and-white film with extended red sensitivity reaching approximately 740nm. It remains fully panchromatic, meaning it behaves normally without filtration, but it responds dramatically when paired with strong red or near-infrared filters.

In practice, this means:

- Green vegetation brightens noticeably

- Blue skies darken

- Skin tones smooth subtly

- Architecture remains structurally honest

Instead of overwhelming the frame, SFX reinterprets it. It’s a film that rewards structure, geometry, and restraint.

Metering Lies, Materials Don’t

One of the defining challenges of working with SFX and deep red filtration is that TTL meters can underexpose by more than a stop. The meter is calibrated for visible light. Infrared doesn’t register the same way.

Rather than fight the meter, this series ignored it.

Exposure decisions were made based on:

- Subject reflectivity (foliage vs steel vs concrete)

- Sky dominance

- Desired shadow density

- Previous frames on the roll

Infrared rewards repetition. As the roll progressed, exposure became more conservative, and the negatives improved.

Time as an Unplanned Collaborator

Because these were daylight exposures stretching several seconds, movement entered the frame whether it was invited or not. People walking through the scene became partial impressions — present, but unresolved.

These “ghost figures” weren’t removed or avoided. They’re a consequence of letting time into the photograph. Infrared already exists outside normal perception; motion blur reinforces that displacement.

In a medium obsessed with freezing moments, these frames allow them to dissolve instead.

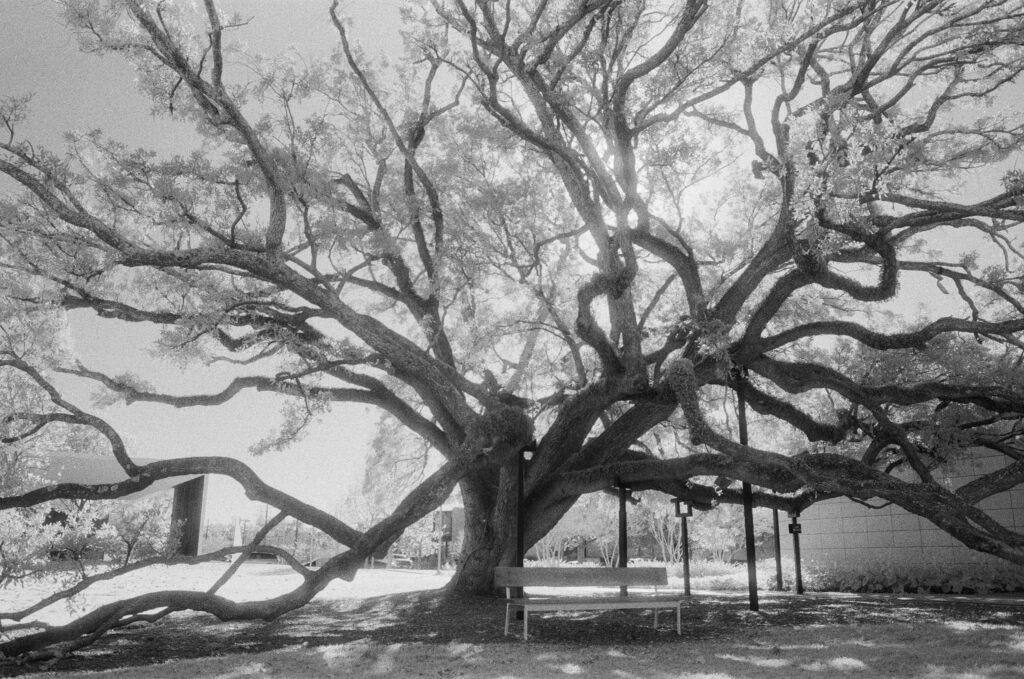

Editing as a Digital Darkroom

The final images were edited in Lightroom — deliberately and transparently.

No presets were used. No attempt was made to fake infrared behavior. Adjustments were limited to:

- Curve shaping

- Contrast refinement

- Local tonal control

The goal was not transformation, but translation — the same role a darkroom plays after development. The negative did the heavy lifting. The edits simply clarified intent.

Why This Is Only Part One

This project is structured as a three-part infrared comparison, using the same methodology across all films. SFX 200 establishes the baseline: controlled, repeatable, near-infrared with structural integrity.

The next films in the series will push further into infrared sensitivity and narrower exposure margins. What changes — and what breaks — will be documented with the same discipline.

The Unedited Negatives

At the end of this post, I’m including all of the original, unedited scans from this roll.

Not as a disclaimer — but as context.

Infrared photography lives and dies in the negative. Editing can refine, but it cannot rescue poor exposure or misunderstanding of the medium. These originals show where decisions succeeded, where they failed, and why the final images look the way they do.

Transparency matters. Especially in analog work.

December 23, 2025

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

@2025 copyrighted | created with brains

Based in HTX | travel Nationwide

jasonr@projectagbrmedia.com

Be the first to comment