Resurrecting a Legend: The Zeiss Ikon Contaflex IV on CineStill 400D

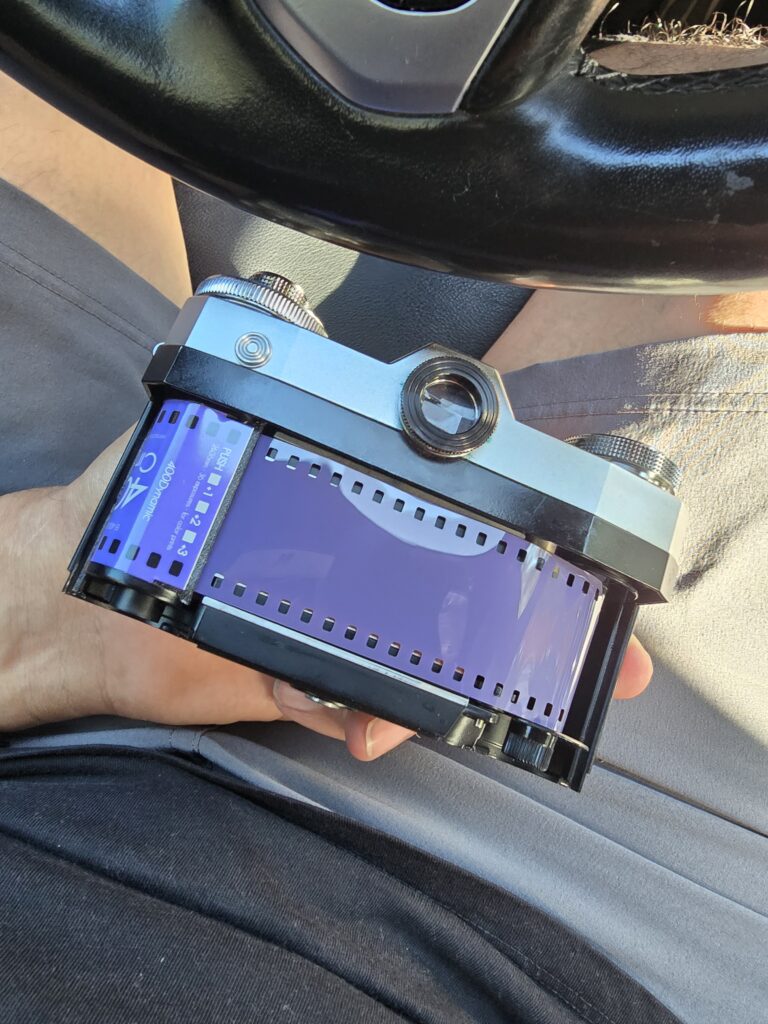

Unedited 35 mm film scans – straight from the Zeiss Ikon Contaflex IV, shot on CineStill 400D.

1. Unearthing the Machine

There’s a certain hum that old mechanical cameras give off — not a sound, but a feeling.

The kind that makes you realize you’re holding something built before the idea of “planned obsolescence.”

This Zeiss Ikon Contaflex IV came out of storage from my partner’s family closet. It had been resting quietly for decades, sealed in a deep-brown leather case embossed with the Zeiss Ikon logo. When I opened it, the smell of aged hide and machine oil hit first — the scent of a bygone era when cameras were made by hand, not algorithm.

The camera’s serial number etched on the barrel, its Carl Zeiss Tessar 50 mm f/2.8 lens still pristine, its leaf shutter eager to wake up again.

I decided to load it with CineStill 400D, the newest daylight-balanced film stock to carry cinema DNA — a fitting modern match for a Cold-War-era optic.

2. The Contaflex IV and the World That Built It

The Contaflex IV was introduced by Zeiss Ikon AG Stuttgart in the late 1950s, part of a long lineage tracing back to the original Contaflex of 1953.

It was the first series of 35 mm SLRs to merge the precision of a leaf shutter with reflex viewing — an engineering challenge that few dared to attempt.

Zeiss Ikon itself had formed in 1926, a merger of Germany’s optical heavyweights: Contessa-Nettel, Ernemann, Goerz, and ICA. Together, they became a powerhouse for precision engineering.

The Contaflex line stood as Zeiss Ikon’s answer to Japan’s emerging SLR competition. Each model refined the formula — from the Contaflex I to the IV — adding a built-in selenium light meter, improved film advance, and faster lenses.

The IV’s Synchro-Compur leaf shutter was unique — it allowed flash synchronization at every speed and produced an almost inaudible click, soft and precise.

Inside, the light meter wasn’t coupled; photographers had to transfer readings manually. A deliberate process — which, in truth, made every exposure earned rather than guessed.

3. Lenses, Engineering, and Legacy

The Contaflex IV came standard with the Tessar 50 mm f/2.8, a four-element lens formula that dates back to 1902. Known for crisp micro-contrast and Zeiss color fidelity, it gives CineStill’s modern emulsion that glowing, cinematic edge.

Zeiss offered front-element interchangeable optics — auxiliary Pro-Tessar lenses at 35 mm, 85 mm, and 115 mm focal lengths — though the base Tessar remained fixed to the body. These accessories turned the Contaflex into a modular system before “mirrorless systems” were even conceived.

Collectors note that the Contaflex IV sits in the middle of the series’ golden age (roughly 1957 – 1959).

A good copy today, like this one with the original case and functioning meter, fetches between $90 – $200 USD, depending on condition. A mint set with auxiliary lenses can exceed $400 on eBay or KEH.

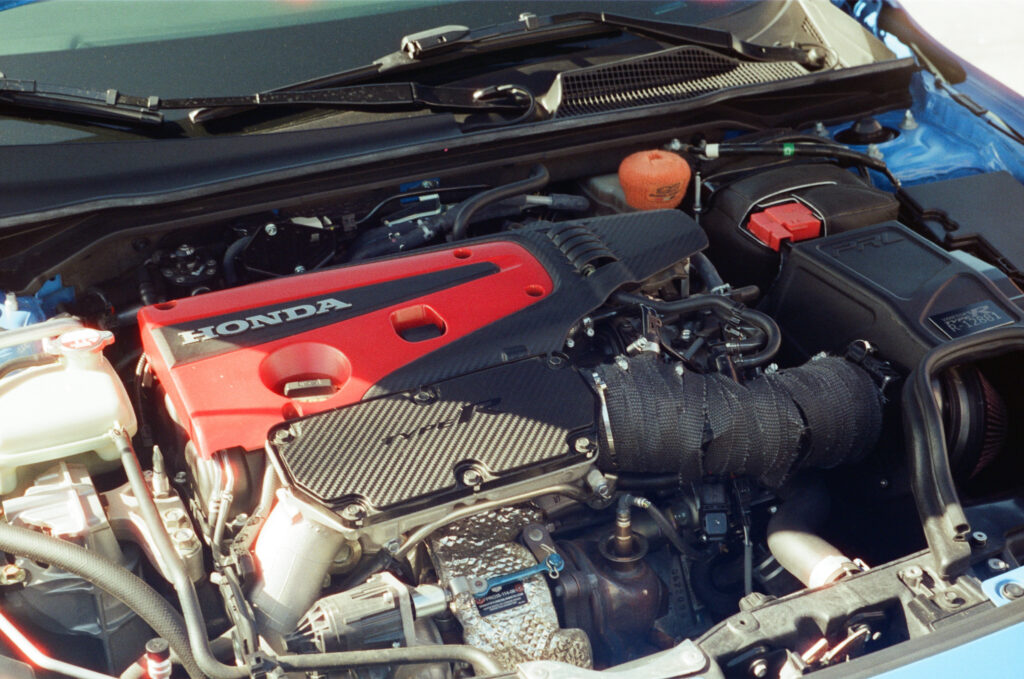

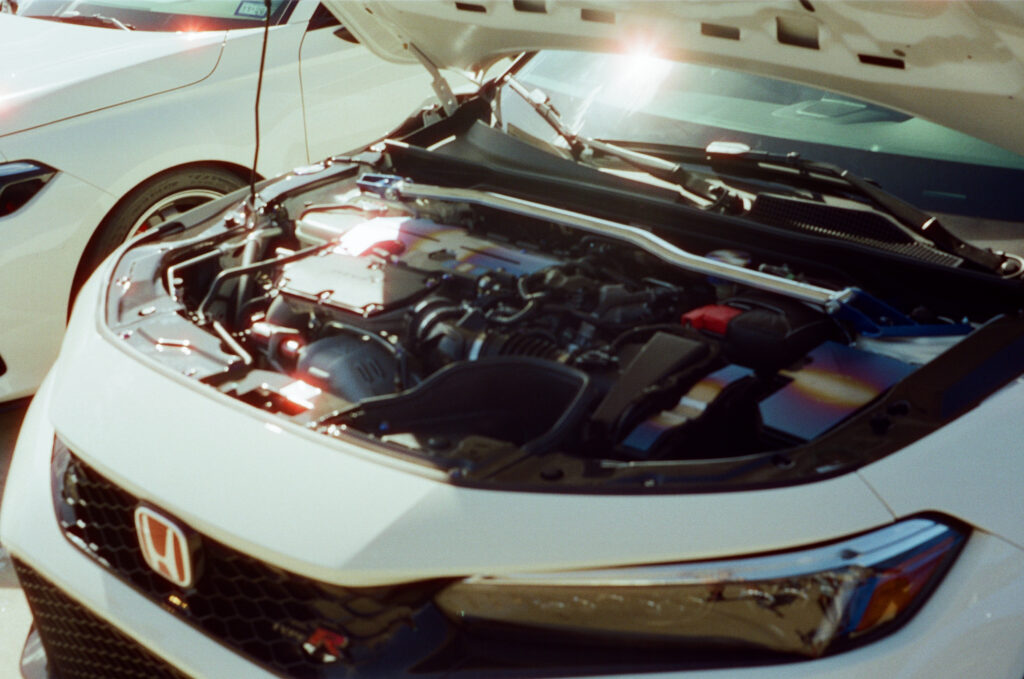

4. The Roll: CineStill 400D in Action

I wanted this test roll to speak for the camera, not for me.

No Lightroom. No color correction. No masking the quirks.

Just raw chemistry meeting raw machinery.

- First frames: Houston’s Coffee & Cars at POST. A white BMW rolling under full sun. Skin tones, paint reflections, shadows — 400D’s daylight stock handled it all.

- Mid-roll: Glenwood Cemetery. Quiet marble and morning light — the Tessar lens rendering the gravestones with crisp whites and soft greens.

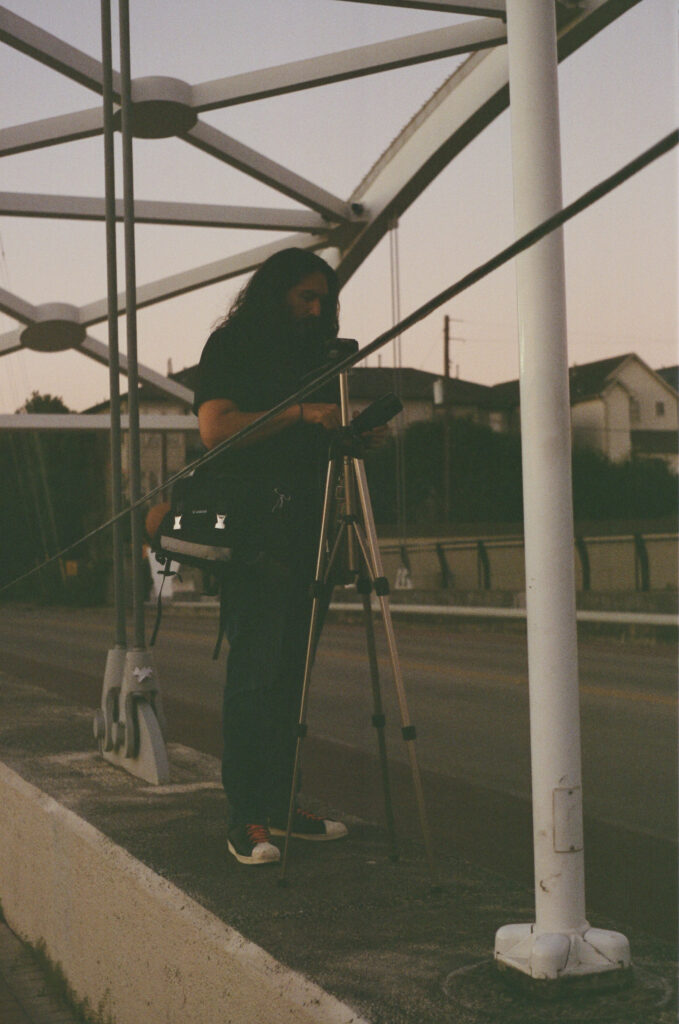

- End of roll: The Sabine Street Bridge at sunset. I looked through my viewfinder and shot the skyline through the rear window reflection of a passing car. Later frames caught a friend working the same bridge at dusk, tripod steady, film winding, patience visible.

- Final shot: The equestrian statue at Hermann Park, bronze against a clouded blue — one of those moments where film grain and human history blend perfectly.

Each image came out as proof: this sixty-year-old Zeiss still breathes light like it was built yesterday.

5. What Survived of Zeiss Ikon

The Zeiss Ikon company we knew eventually fragmented.

In 1972, facing Japan’s rising dominance in optics, Zeiss Ikon AG shuttered its Stuttgart operations. The Zeiss name lived on through Carl Zeiss Oberkochen, which focused on lenses, microscopes, and scientific optics.

Today, the spirit of Zeiss Ikon endures in Carl Zeiss AG (Germany) and Zeiss Camera Lenses (still producing the Planar, Sonnar, and Tessar descendants).

A brief revival came in 2004 when Cosina, under Zeiss license, released a new Zeiss Ikon rangefinder — a spiritual echo of this Contaflex heritage.

The brand may have dissolved, but the mechanical soul still clicks on in every restored body.

6. The Feel of It

Holding the Contaflex IV is tactile poetry.

Film advance has weight, shutter release has feedback, aperture clicks with precision.

Even winding the counter to zero feels ceremonial.

It’s not about nostalgia; it’s about connection — a handshake across time with a craftsman who built something meant to outlast him.

The photos prove it: the film’s halation, the lens flare, the softness of CineStill under daylight.

This isn’t imperfection — it’s humanity printed in silver and dye.

7. What Comes Next – Part 2

Next up: a full black-and-white session using Mummy ISO, the experimental monochrome film stock that’s been sitting in my fridge.

The same Contaflex, same deliberate pace — but this time chasing tone, not color.

No filters. No flash. Just shadow, texture, and time.

November 4, 2025

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

@2025 copyrighted | created with brains

Based in HTX | travel Nationwide

jasonr@projectagbrmedia.com

Be the first to comment